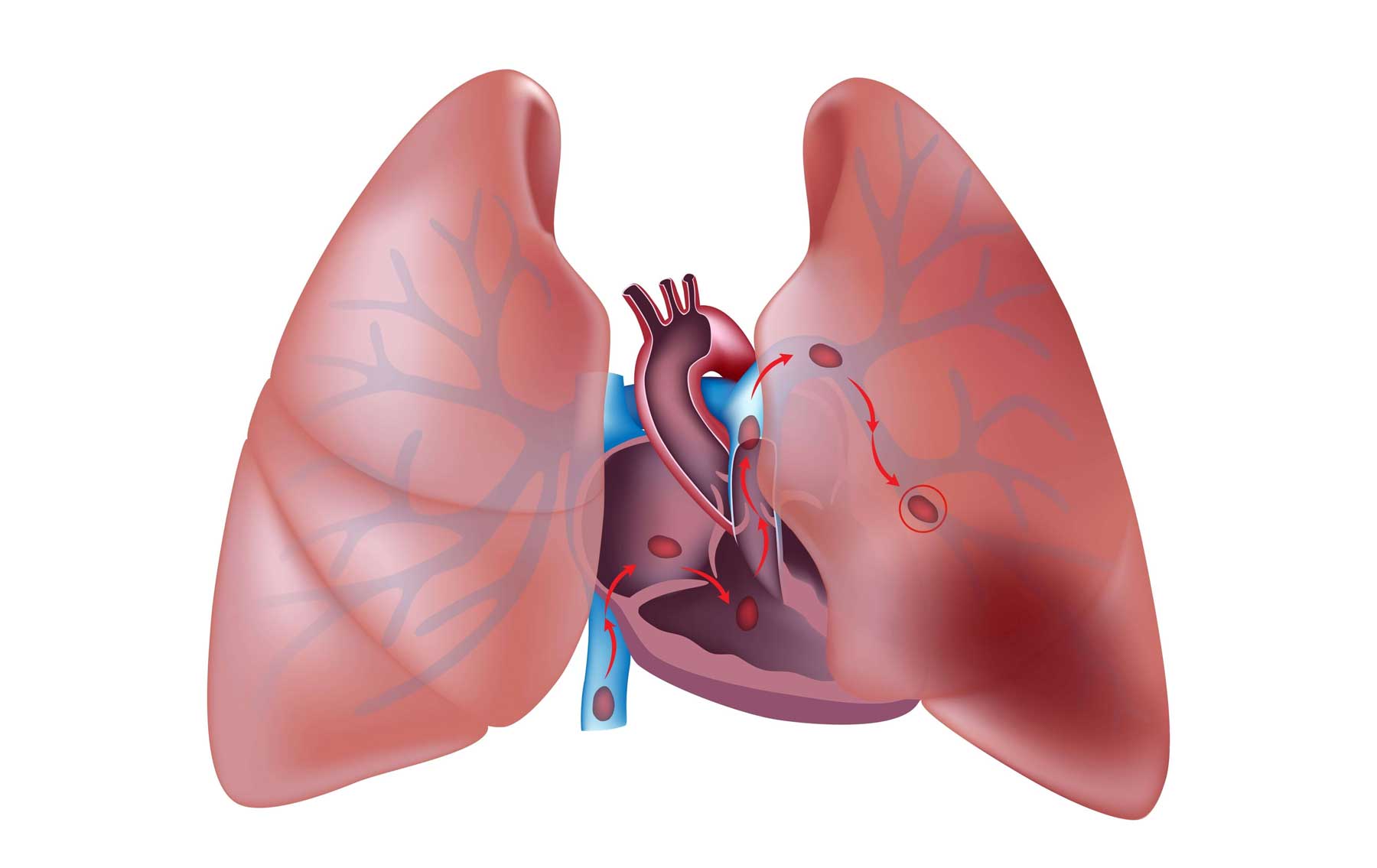

Deep Vein Thrombosis Thrombosis is the formation of a blood clot (thrombus), which can partially…

Aneurysms

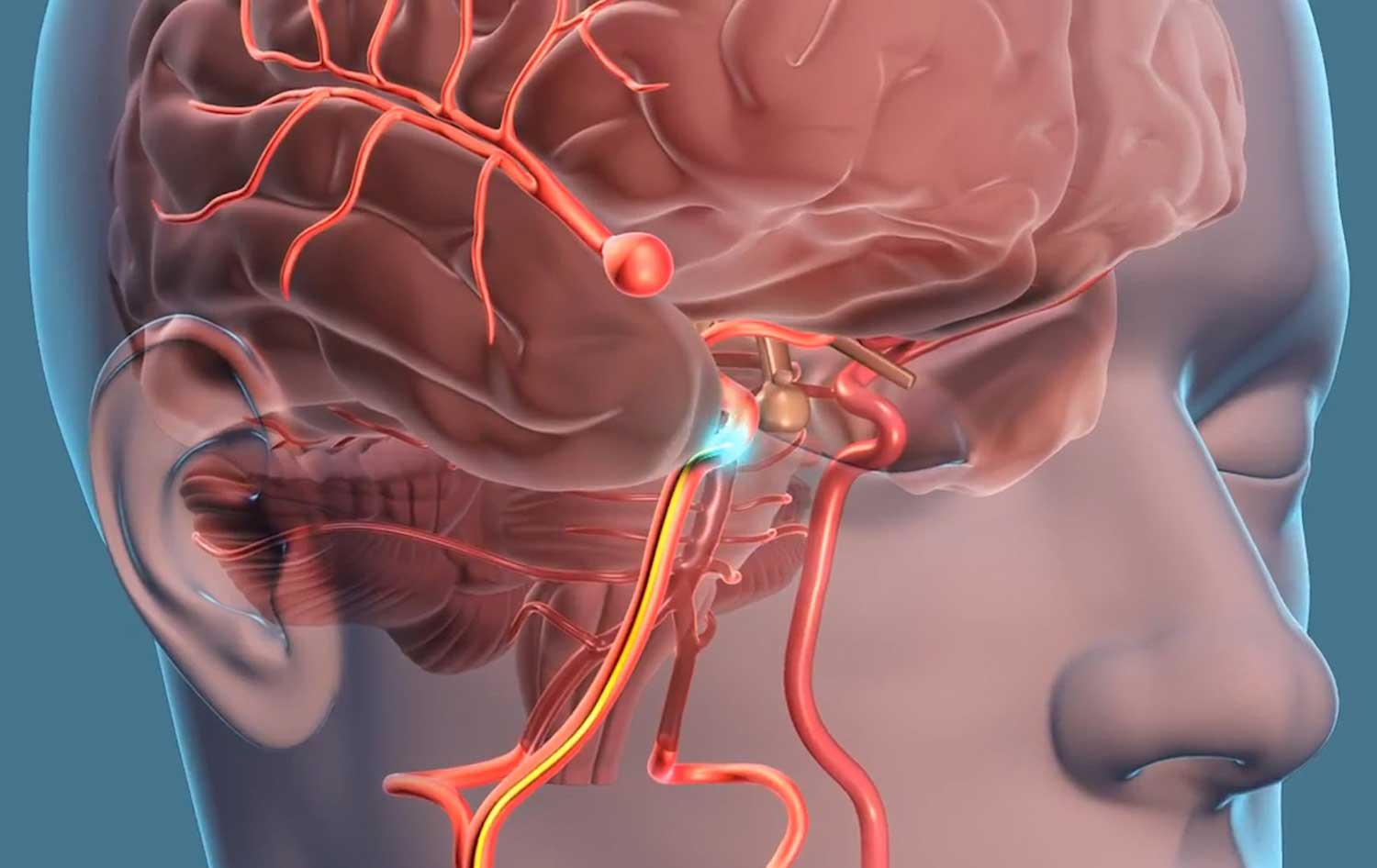

An aneurysm is an abnormal ballooning of a damaged or weakened area in an artery wall. If part of an artery wall is damaged or weakened, the force of blood flowing through the artery may cause the affected area to balloon outward. Although aneurysms can form in any artery, they usually form in the aorta (the main artery in the body) or in arteries in the brain. An aneurysm can develop for any of the following reasons:

- Defective artery wall. An artery wall has an outer, middle, and inner layer of tissue. In some people, the muscular middle layer, which provides support and strength to the artery, has a congenital (present at birth) defect that makes it thin and weak. As blood flows through the defective artery, it may produce a saclike swelling (called a saccular aneurysm) at the weakened area. This type of aneurysm occurs most often in men and in people who have close relatives (especially parents or siblings) who have had an aneurysm, indicating a genetic component. Aneurysms caused by congenital defects usually form in the arteries at the base of the brain.

- Inflamed artery. Inflammation caused by disorders such as infective endocarditis, polyarteritis nodosa, or syphilis may weaken part of an artery wall. If the cause of the inflammation is unknown, the condition is called arteritis. Normal blood flow through the inflamed artery can cause the weakened section of the artery wall to bulge.

- Damaged artery wall. A portion of the muscular middle layer of an artery wall may slowly weaken as a result of a chronic (long-lasting) condition such as atherosclerosis. An aneurysm caused by atherosclerosis is usually a ballooning of both artery walls along a short length of the artery (called a fusiform aneurysm). High blood pressure can accelerate damage to artery walls and is often a factor in the formation of aneurysms. Increased blood pressure in an artery can stretch the artery wall in various ways. In some cases, the layers of the artery wall split and blood flows between them, causing a bulge (called a dissecting aneurysm) in the artery wall.

The main risk of an aneurysm is that it might rupture and cause severe internal bleeding, depriving tissues and organs of oxygen and vital nutrients. If the bleeding significantly reduces the volume of blood in the body, the entire circulatory system could stop functioning. Without immediate medical help, a ruptured aneurysm in the aorta is usually fatal.

An aneurysm that does not rupture can disturb blood flow, creating turbulence that can lead to the formation of a thrombus (blood clot). Tiny pieces of a thrombus (called emboli) can break away and travel through the bloodstream, blocking smaller arteries and damaging tissues and organs. An aneurysm that forms in the ascending aorta may stretch the aortic valve in the heart, causing aortic insufficiency. Aneurysms can also grow and press on and damage nearby organs, nerves, blood vessels, and other tissues.

Risk Factors

Because atherosclerosis and high blood pressure damage artery walls, people who have these conditions have an increased risk of developing aneurysms. Following a healthy lifestyle—including eating a low-fat diet, exercising regularly, not smoking, and managing stress—and taking cholesterol-lowering drugs or antihypertensive medications can help prevent or slow the progression of atherosclerosis and help keep blood pressure under control, thereby decreasing the risk of aneurysms.

Symptoms

Symptoms of aortic aneurysms depend on the type of aneurysm, the section of the aorta affected, and the structures the aneurysm presses on. Saccular or fusiform aneurysms usually do not cause symptoms. However, if a large aneurysm forms in the thoracic aorta (the portion of the aorta that passes through the chest), it may cause chest pain, back pain, hoarseness, shortness of breath, difficulty swallowing, or a persistent cough. A dissecting aneurysm in the thoracic aorta usually causes severe chest pain and shortness of breath, and may be mistaken for a heart attack.

A large saccular or fusiform aneurysm in the abdominal aorta (the portion of the aorta that passes through the abdomen) is often visible as a pulsating lump on the surface of the abdomen. If the aneurysm is toward the back, it may press on the spine and cause severe backache, especially if the aneurysm expands or ruptures. Dissecting aneurysms of the abdominal aorta are rare. When they develop, the main symptom is severe abdominal or intestinal pain.

Although aneurysms in the peripheral arteries of the arms and legs are not common and are not considered dangerous, an aneurysm that forms in the artery behind the knee can suddenly clot, blocking blood flow and causing gangrene of the leg.

If you have symptoms of an aortic aneurysm or if you notice an unexplainable lump anywhere on your body, especially on your abdomen, and particularly if it throbs, see your doctor right away. Most people who have a ruptured aneurysm die before they can get emergency medical treatment.

Treatments

The usual treatment for an aneurysm is surgery to repair or replace the affected portion of the artery with a tiny plastic tube. In people who do not have other health problems, most elective surgical procedures performed on aneurysms in either the thoracic (chest) or abdominal aortas are successful.

If an aneurysm in the thoracic aorta can be treated with surgery, chances of recovery are very good. If the aneurysm cannot be treated surgically, chances of survival are poor. In general, small aneurysms in the abdominal aorta are not life-threatening and usually do not require immediate treatment. Aneurysms in the abdominal aorta are removed surgically only if they are large or are expanding. Before recommending surgery, a doctor will usually monitor the aneurysm with ultrasound or CT scanning to determine how rapidly it is expanding. If a person is in generally good health, elective surgery on a large or rapidly expanding aneurysm carries far less risk than emergency surgery performed after the aneurysm has ruptured.

In a procedure called stent grafting, the doctor inserts a thin, flexible wire into an artery in the groin area and, observing the aorta on a video monitor, threads the wire to the aortic aneurysm. He or she then guides a tiny tube called a stent along the wire to the aneurysm. Once the stent is inside the aneurysm, the doctor expands it until it bridges the area of the aneurysm. By providing a sturdy new channel for blood flow, the stent relieves pressure on the weakened artery walls.