innovative techniques

Platelet-rich plasma therapy

Times have changed since the days of bloodletting, when doctors treated their patients by taking blood out of them. Now a procedure called platelet-rich plasma therapy has emerged that involves injecting a portion of the blood back into an ailing joint. You might say it’s bloodletting in reverse.

More doctors are beginning to offer platelet-rich plasma therapy to their patients as a way to treat joint problems caused by damaged and inflamed tendons. It is being used as an alternative to surgery in some cases and as an adjunct to speed healing in others. So far, research and use of the technique has been geared toward tendons, but treatment of muscle and bone problems is a possibility.

Joint pain and injuries often linger, whether you’re an elite athlete or a weekend warrior, so the prospect of a new treatment is exciting. The simplicity of platelet-rich plasma therapy adds to its appeal, as does the lack of any obvious dangers thus far.

Healing power

Tendon tissue has a low metabolic rate that makes it slow to mend. In theory, the injection of platelet-rich plasma could make up for that natural tendency and, in so doing, harness the blood’s own healing powers. Indeed, some researchers have reported positive results when they injected whole blood, not just platelet-rich plasma. (Kolata, for example, ended up getting an injection of whole blood — not, as she originally planned, platelet-rich plasma.) A Spanish group has come up with its own way of preparing platelets that involves treating them with sodium citrate and calcium chloride. They claim their technique produces more growth factors, and they’ve dubbed their version PRGF, for “preparation rich in growth factors.”

Proponents of platelet therapy say there’s little chance of the body reacting to the injections with an inflammatory or immune response because the person’s own blood is being used as the source material. They also tick off the advantages over surgery — little or no pain, faster recovery, no scar tissue. That may all be true, but there also hasn’t been any study done to make a good side-by-side comparison to surgery. And, of course, surgery isn’t the only alternative to platelet therapy.

Joint Replacement

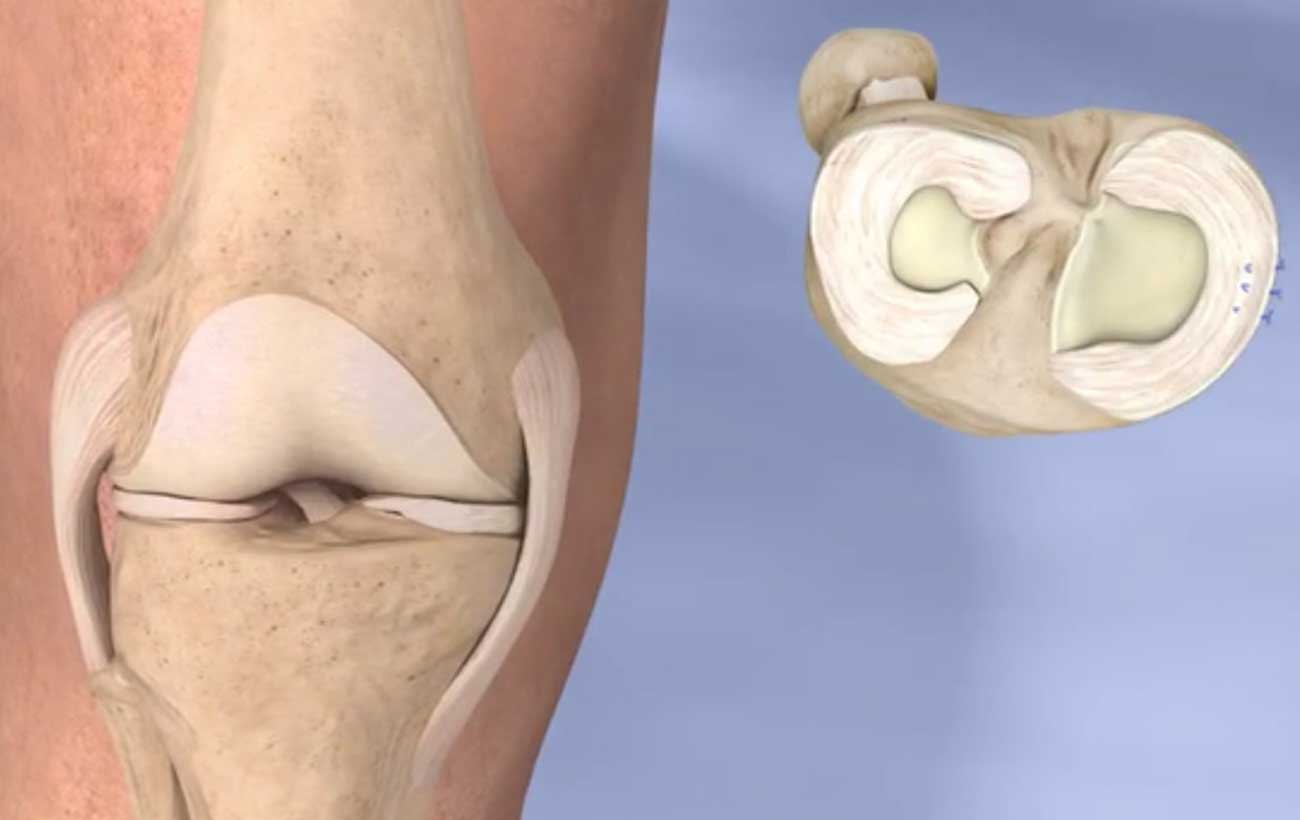

Joint replacement means removing part or all of a damaged joint and installing hardware to allow the limb to move without pain or limitations. The replacement hardware is called a prosthesis. These are made of plastic, metal, ceramic, or a combination of these materials. Most joint replacements are performed to treat damage from arthritis to the knees or hips. Orthopedic surgeons do the procedure under general anesthesia.

The decision to replace a joint depends on several factors:

- How bad are the symptoms? Moderate to severe pain, stiffness, and limited function of the joint may indicate the need for a new joint.

- How bad is the damage to the joint? An x-ray or other imaging test can show if the bone and cartilage in the joint have deteriorated. The joint may also become misaligned. Moderate to severe joint damage is an indication for joint replacement.

- Does the joint problem limit daily activities and compromise a person’s quality of life? This, too, indicates that joint replacement may be beneficial.

Like any major operation, joint replacement surgery carries the risk of possible complications. For example, there are small risks that you may have a reaction to the anesthesia, develop a blood clot, or contract an infection.

Age by itself does not prevent a person from getting a new joint, but being overweight or having a chronic health condition, such as heart disease, might raise the risks. It’s also possible for the prosthesis to break, making it necessary to do a so-called revision procedure to fix it.

A hospital-stay of a day or two is typical for knee or hip joint replacement. Physical therapy then helps the muscles around the new joint to get strong. Joint hardware can last 15 to 20 years or more, depending on the type and the person’s level of physical activity.