Color vision deficiency (also called color blindness) is a vision disorder in which a person…

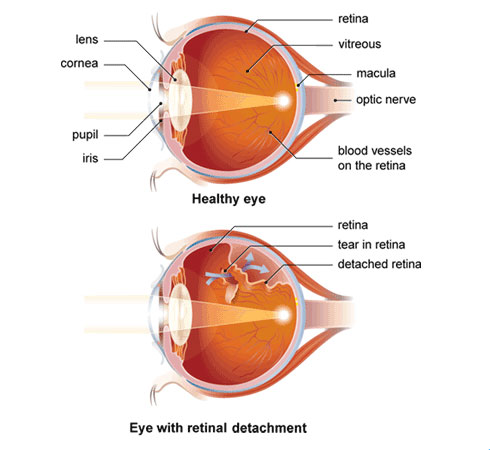

Retinal detachment occurs when the retina—the light-sensitive membrane that lines the inside of the back of the eye—lifts away from the choroid, the layer of blood vessels beneath the retina that supplies the eye with oxygen and nutrients. In most cases, detachment occurs after a hole or tear that has formed near the front edge of the retina allows vitreous fluid (the substance that makes up the mass of the inside of the eyeball) to seep between the retina and the choroid, detaching the retina. The hole or tear forms either as a result of degeneration of the retina or because the vitreous fluid has shrunk away from the retina and torn it.

If not treated, this process continues until more and more of the retina lifts away from the choroid. Eventually, the retina is attached only at the front of the eye (to the ciliary body) and at the back of the eye (to the end of the optic nerve). Retinal detachment may affect both eyes, but rarely at the same time.

Retinal detachment is a rare condition, affecting middle-aged and older men and women in equal numbers. People who are nearsighted have an increased risk of retinal detachment because the retina is stretched abnormally by the elongated shape of the eyeball. Other risk factors include eye injury and having a lens removed for treatment of a cataract. If the disorder is left untreated, a person can lose vision in the affected eye.

Treatments Retinal Detachment

If an ophthalmologist detects a hole or tear in the retina before detachment begins, he or she may repair the tissue using either cryosurgery (freezing) or laser photocoagulation (in which a highly concentrated beam of light is used to seal or destroy the area around the tear). Both treatments are used to secure the retina to the eye and can be performed using either a sedative or a local anesthetic in a doctor’s office or in an outpatient facility.

If detachment has already begun, an ophthalmologist may recommend a surgical procedure called scleral buckling, in which the fluid between the retina and choroid is drained to allow the retina to fall back into place against the choroid. The hole or tear in the retina is then sealed and a silicone band is sewn around the eye to securely attach the sclera (the white of the eye) to the retina.

In a procedure called pneumatic retinopexy, the doctor injects a small gas bubble into the vitreous fluid to push the retina back against the choroid. These procedures may be done either in a hospital or in an outpatient facility using either local or general anesthesia.

Your vision will probably return to normal if the procedure is performed before detachment has begun or if the detachment is limited to the front edge of the retina. If the detachment is more extensive and your central vision has been affected, your visual field and central vision may be permanently impaired to some extent.

After retinal detachment in one eye, there is a significant risk that the condition will develop in the other eye. For this reason, you should see your ophthalmologist as often as he or she recommends to watch for any weak areas in the retina.